Abortion Saved My Mind, and My Life

The under-discussed mental health effects of pregnancy in a post-Roe world.

The author of this piece is a woman in her 30s living on the West Coast who has asked to remain anonymous.

Before I knew I was pregnant, I thought I was having a mental breakdown.

Every problem and conflict felt like the worst thing that had ever happened to me. I couldn’t regulate my emotions. I hadn’t been suicidal in over a decade, but those neural pathways were well worn, and I found myself almost comforted to walk them again. Almost, because the onset of those feelings was so sudden, and so alien. I was always tired, and eating became an awful chore. I started researching brain tumors and neurological disorders.

But I wasn’t sick. I was late.

In my haze of misery and mania, it took days to notice, but only seconds for a home pregnancy test to confirm it. It felt impossible, and stupid, and funny. I called my husband and told him we were finally getting me the abortion I’d always wanted—a crass inside joke, a monkey’s paw curling its finger.

I never wanted children, but always wondered what would happen if the hypothetical became real. It was a secret fear: that my years of swearing off motherhood would be thrown over by some primal force, that I would be changed and overpowered by maternal feelings. I downloaded a pregnancy app and it estimated that I was five weeks, which meant my baby was the size of a sesame seed.

I felt no love, no connection, no divine feminine energy. Mostly, I was indignant that something so small could so thoroughly wreck my mental health. Morning sickness and mood swings were common enough first-trimester tropes, but what I was living through felt totally out of proportion to the pregnancy narratives I knew. And the symptoms I was experiencing were separate and apart from my feelings about the pregnancy itself. Even if I had wished for this, planned for this, I would still feel powerless and crazy. I would still want to die. If anything, knowing about the pregnancy made me feel better, because I finally knew what was wrong with me.

It turns out, mental illness during pregnancy is fairly common. A 2006 study found that 10 to 15 percent of women experienced clinically significant depressive symptoms during pregnancy, and only a third of the pregnant women who met the criteria for major depression received any treatment for it. Other studies estimate that around 20 percent of pregnant people experience anxiety or depression during their pregnancy.

Reading statistics was one thing, but I wanted a frame of reference that felt personal. I reached out to a close friend who was entering her second trimester, and when I told her that I was pregnant and losing my mind, she immediately understood. She was already “pro-choice” and had an abortion years before, but said keeping a pregnancy is what truly radicalized her. She was exhausted, and emotionally fragile, and struggling with a demanding, stressful job amidst a growing list of pregnancy symptoms. The whole ordeal was only made worth it by the love and hope she felt for her baby.

I also turned to online communities about pregnancy, where I found posts that I could’ve written myself:

“It’s amazing how quickly hormones can make you feel like you’ve lost control.”

“I currently feel no attachment to the fetus that is making me wish I was dead.”

“Like I'm in an endless black hole of despair and everything around me is collapsing.”

Many described their struggle to find pregnancy-safe psychotropic medications that worked. I wasn’t on meds when I got pregnant, but for the first time in years, I considered it. Had I decided to keep the pregnancy, that decision would be colored by anxieties around birth defects and fetal development. The pregnant patient “is perhaps the last true therapeutic orphan” because fears of harming fetuses have historically limited research into drug treatment of maternal mental illness.

Finding the right medication can be lengthy and arduous, even when you’re not pregnant. Weaning off can be even harder and more time intensive. And in pregnancy, timing is everything. I quickly learned that the clock starts ticking fast -- not at the date of conception, but the date of your last period. Every week, the “orderly and intricate process” of fetal development builds tissues and organs and bones. The sesame seed becomes a watermelon seed, and then someday, a melon. If you let it grow.

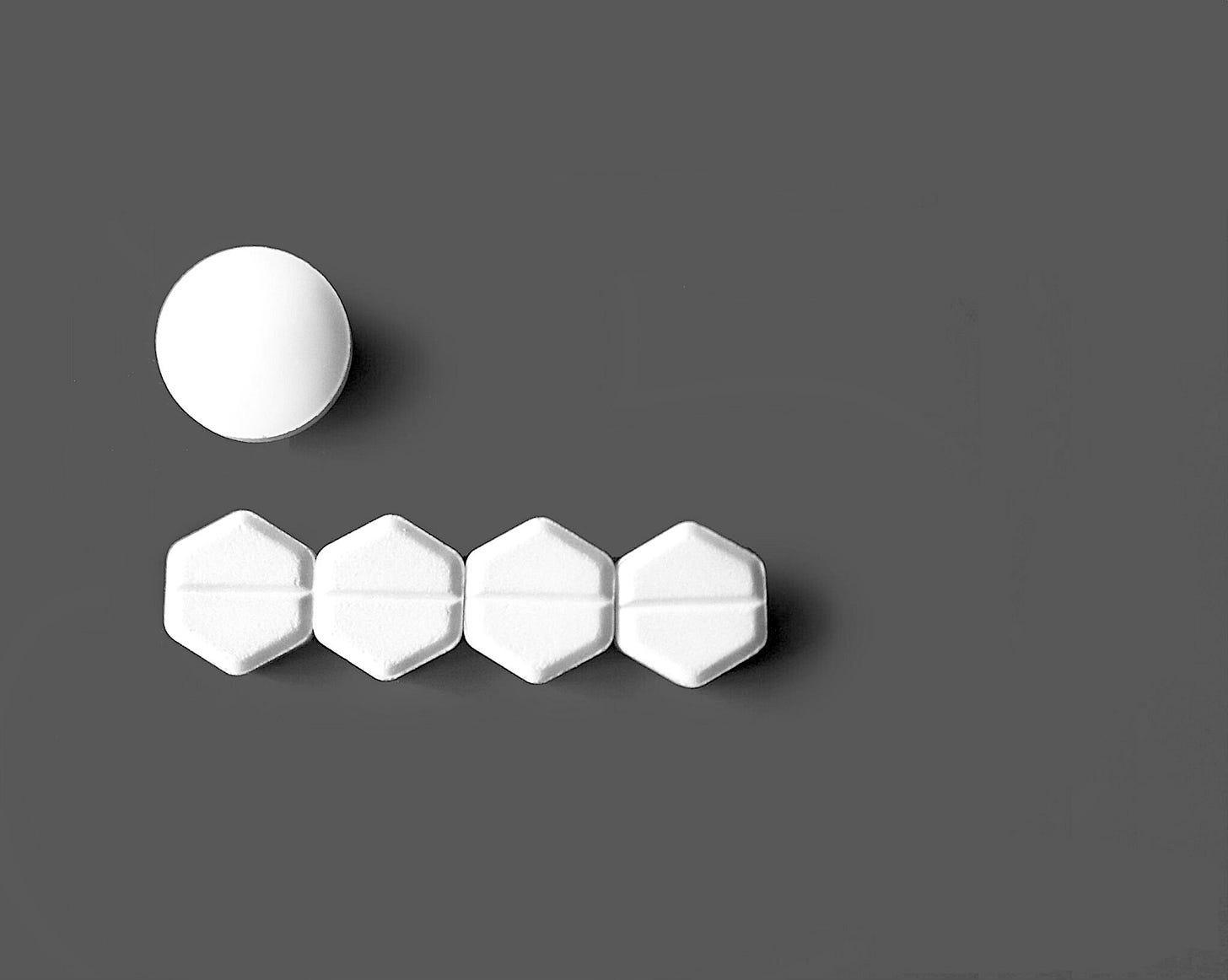

When I went to Planned Parenthood to get misoprostol and mifepristone, the nurse asked if I wanted to see the ultrasound. I instinctively resented the question, which has long been a tool of anti-choice advocates to guilt patients into backing out of their abortions. Still, I was curious, and the nurse was just trying to do her job. For some, it might be a chance to say goodbye, or a final step to know they were making the right decision. In the end, I couldn’t think of a good reason to say no.

It didn’t look like anything, seed or fruit or otherwise. It didn’t make me cry, or question. I swallowed the first pill to stop the pregnancy, and took the other four home with me to get it out.

The abortion was excruciating, the kind of pain that makes it hard to see straight. It was worse than my worst menstrual cramps, worse than my most elaborate tattoos. But even now, thinking about the relief I felt when it was over, I get choked up. At first, it was just the relief of not being pregnant, of knowing that I made the right choice. But within a few days, as my bleeding slowed and my energy returned, my old inner voice came back too. After weeks of confusion and terror, I could understand my emotions, and where they came from. I could follow conversations, and see the world outside myself. My body was mine again, but so was my mind.

It felt like a miracle, albeit a private one. I didn’t want my ordeal to be idle gossip, but keeping it a secret felt strange too. It also felt political in the wake of Roe’s unraveling, so I awkwardly stumbled through conversations with trusted friends, trying to impress upon them that the abortion was hard, but the pregnancy was torture.

My pregnancy gave me a profound respect for anyone who has ever managed to bring a baby into this world. It also gave me a righteous, blinding anger towards anyone who has ever tried to force someone to do it. If I had lived in a state where abortion was illegal, I would’ve done anything in my power to have one anyway. And if I was too poor, or too mentally fragile to endure the gauntlet of travel and surveillance and anti-choice activism, I wouldn’t have had a baby. I would’ve killed myself.

Damn. So much respect for this writer.

holy shit. this is one of the most powerful and deeply painful personal essays I've ever read about depression and unexpected pregnancy. and a chilling glimpse into how it must feel to be walking around with a uterus in these early days of the American handmaid's tale that roughly a third of the population wants to inflict on the rest. mad respect for the writing itself and for the brave heart and clear eyes of the writer.