Against Grief as Political Currency

Palestinians have been forced to use their grief to mobilize movements. What happens when we turn away?

by Keyvan S.

Keyvan S. is a writer living in Los Angeles and runs the Substack Persian Breakfast.

Over two million likes. More than one-hundred-thousand replies. A top comment reads, "This is the most heartbreaking video ever. This poor baby." The Instagram video, posted on November 6th by the Palestinian photojournalist Motaz Azaiza, shows footage of a boy, at most 3 or 4 years old, sitting on a hospital bed in Gaza. His hair and face are grayed with dirt. He has just been pulled from the rubble of his home. Trembling in fear he turns to another boy, a few years older and bloodied, and shows him the cuts on the inside of his palms. Another comment says: “I am sorry that the world is watching and not helping. I’m so sorry.”

In the last two months, as we have watched Israel unleash an unprecedented and genocidal campaign of violence upon Palestinians, grief has permeated so many of our lives, even if we live on the other side of the world, or have no direct connection to Gaza. In this context of ubiquitous loss, which as of this writing surpasses 22,000 lives, there is no luxury of time for mourning. Instead, Palestinians must parade their grief in front of cameras, using precious internet and energy to beg the international community to mobilize on their behalf. Grief, in other words, has become the primary political currency for securing compassion and action.

The philosopher Judith Butler says that loss makes a “tenuous “we” of us all,” because it is an unavoidable human experience, one that can therefore serve as the basis of political solidarity and mobilize activism. There is a grim logic to this exercise. We understand loss and grief to be universally shared experiences, making them affectively useful tools to engender political will. As we look at the images of grieving families from Gaza, their grief propels us to want to take action, to do something to halt this gross display of indifference to human loss.

Undoubtedly, this turn to activism in the face of unbearable, human-engineered tragedy is imperative. At the same time, though, we can’t afford to predicate solidarity on suffering that results from the extraordinary, therein precluding the quiet violence that afflicts the everyday. A politics of solidarity galvanized by spectacular displays of loss and grief can be strategic and effective in the moment. But such approaches to grief can also render invisible the more quotidian forms of violence—the “slow deaths” caused by the grinding violence of settler colonialism—that do not constitute spectacles. Political movements that spring into existence in reaction to the spectacular usually have a short shelf life; once the spectacle is gone the solidarity tends to dissipate too.

***

Under ordinary circumstances, we consider grief a personal and private response to loss, an inherent fact of life. When loss happens at a sociopolitical level, however, we feel compelled to politicize grief.

I was born in Iran, and spent the first 17 years of my life living there. When I left, my parents stayed behind. My father died in Iran in 2017, while my mother lives there to this day. As a writer, I often comment on American foreign policy vis-a-vis Iran. Many of these conversations, in the last few years, have specifically revolved around the role of sanctions, which I am told are the only peaceful alternative to military warfare.

When publicly confronted with questions about the morality and practicality of sanctions, I often grapple with questions surrounding my own grief. Should I, for instance, delve into the more nuanced aspects of my dad’s death? Should I mention that his death was not a “normal” one; that perhaps he would be alive today if U.S.-imposed sanctions on Iran had not restricted my family’s access to life-saving medicine; and that I have to live with the political significance of his death day after day?

Damned if I do, damned if I don’t. If I fail to mention the details of my father’s death, my opposition to sanctions lacks personal authority. If I do, I have to dig into a private part of my being to repurpose my grief politically. In either case, this is emotionally excruciating work. I’d much rather my father were alive today than have to narrate his agonizing death in the hopes of organizing opposition to American foreign policy. Nonetheless, I have to return to my grief time and again. I have to relive it each time. I have to treat it like a strategic asset, rather than a private part of my being that should not be politicized, a tragedy that should wholly belong to me.

Over the years, I’ve learned to placate the psychic pain by telling myself that all activism demands that the activist transforms their pathos into protest. Moral injustice definitionally implies a privation—something is not normal somewhere due to the lack or loss of justice. Therefore, all injustice is an occasion for grief, and in turn demanding justice requires a transformation of grief into grievance. At the same time, I have to remind myself that this political transformation requires time and space for the aggrieved to grieve. It did for me, at least. Mourning is a temporal process; a ritual of healing and acceptance that presupposes time.

But not for Palestinians. In the face of unyielding violence and loss, Palestinians are rarely afforded the temporal privileges of mourning. As Abdaljawad Omar poignantly writes, “the Palestinian collective endures within a temporal chasm, wherein the durée—essential to the rites of mourning—is systematically arrogated and denied.” The enactment of grief demands time, the ability to begin a process of mourning that spreads across days, months, even years. However, this possibility is always foreclosed for Palestinians, Omar posits, because time is an unattainable luxury amidst relentless and recurrent bereavement. Within this landscape of loss, marked by unremitting death, Palestinians cannot grieve their dead because, in the words of Devin Atallah, “we are obligated to steal our present to fight for our future.”

For Palestinians, this tradeoff between grief (inhabiting the present) and grievance (fighting for the future) is not a choice. There is simply no time to privately grieve the dead while a heavily militarized occupation encroaches on the access to life. Instead, Palestinians report on their grief, as Wael Al-Dahdouh and Motaz Azaiza do. They relocate grief from the private realm to the public domain, attempting to render it legible, to publicize the suffering that they witness up close daily.

Making grief publicly visible as a means of provoking anger can sometimes incite the multitudes into action. It has before, and it is partially serving that utilitarian function in this moment too, as people from disparate backgrounds are organizing into a unified demand for a ceasefire. In the age of social media, we just can’t avert our gaze from the images of mangled bodies—adults and children alike—flooding our feeds. The pictures attempt to vivify war and its savagery, forcing us to take in the insanity of an unprecedented situation brought about through military wrath. We fixate on the image, the spectacle. We acknowledge that this is a moment that uniquely demands solidarity in the face of unspeakable barbarism, and we rely on the spectacle to humanize the unspeakable.

However, we need to interrogate the integrity of this exercise. It is us, the Western onlookers, who expect that Palestinians exchange their misery for our mercy. It is us whose solidarity demands close-ups of horror and grief; whose activism is most effectively maintained through public displays of infernal cruelty. For better or worse, our attention tends to wane when it is not focused on the sensational and the spectacular—especially in a world where the news cycle moves with such rapidity that yesterday’s tragedies conveniently get buried under today’s tabloids. And what happens then? What happens to the Palestinian families once their dead are no longer newsworthy? Who will rebuild their homes? Who will tend to their wounds? Who will parent their orphaned children? Will Western solidarity persist, or will it move on in the search of new tragedies to gorge on?

In the long term, this approach to solidarity is not sustainable. The development of our moral imagination should not rely on the affective power of Palestinian death. And how much death before our moral capacities become desensitized to the spectacle of suffering? More importantly, though, grief has to be privately attended to before it can be politically communicated. This is a nonnegotiable precondition for repurposing grief to mobilize an enduring politics of solidarity; that the aggrieved have the time to mourn first.

***

“They say that time heals all wounds. It does not,” Sybrina Fulton, Trayvon Martin’s mother, observed on the 10th anniversary of her son’s murder. “Had the tragedy not been so public, I probably would have taken more time to grieve, but I wasn’t given that type of privilege.”

The unrelenting ubiquity of death in Black communities has made mourning and grief central to Black political mobilization. The NAACP using lynching photographs to induce public outrage in the early twentieth century, or Mamie Till-Mobley’s insistence on an open-casket funeral for her son Emmett, or the footage of the merciless murder of George Floyd in 2020 are a few prominent examples.

But in her latest book, political philosopher Juliet Hooker situates this template in the history of American mobilization for racial justice. For Hooker, the demand that activism be sourced from grief—in particular Black grief—has a robust history dating back to the 1800s. Drawing on this history, Hooker acknowledges the importance of balancing grief against grievance, but also cautions against acceding to the cultural expectation that grief be continually politicized for activism.

According to Hooker, repurposing of grief as grievance inherently demands a tradeoff between attending to loss and eliciting solidarity. For example, using images of the dead to spur political mobilization is an important means for focusing public attention on systemic injustice. But there is an inherent risk here. Solidarity that is tethered closely to visual representations of suffering can reinforce the impression that moral or political redress is only achievable through displays of stupendous death and destruction. Thus, spectacular loss becomes the mainstream currency with which the oppressed can acquire compassion and solidarity.

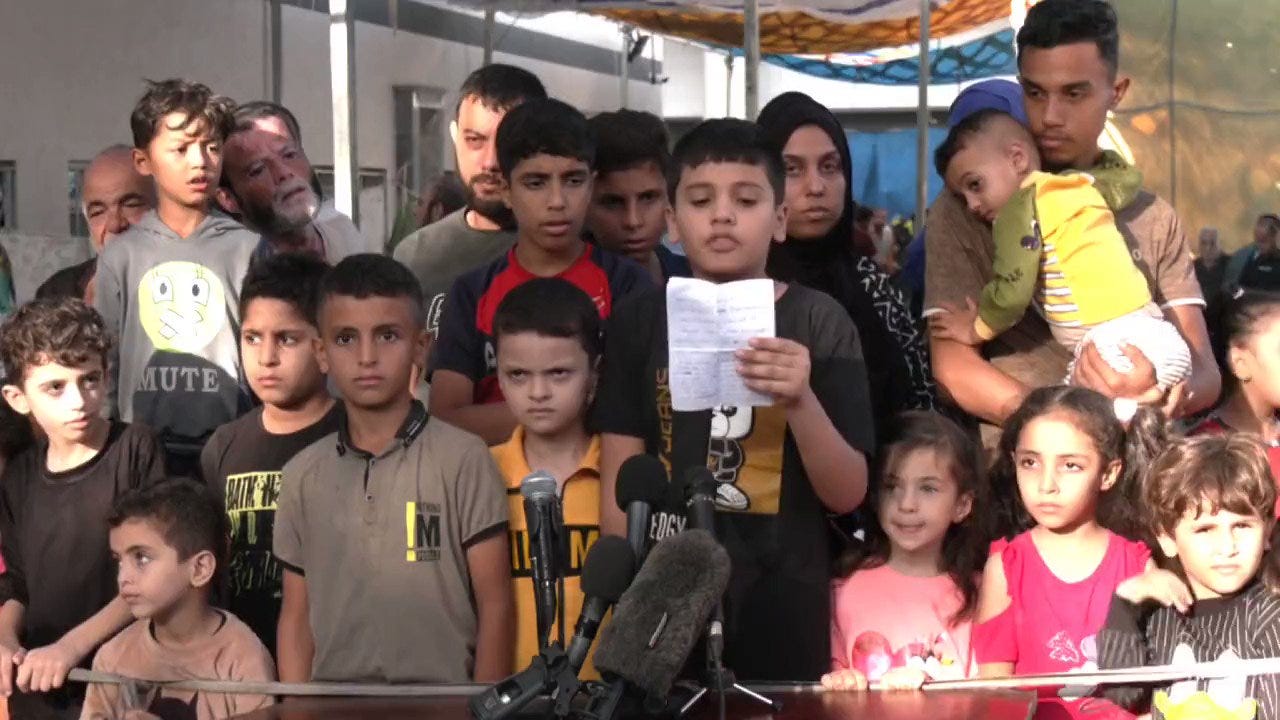

In the present context, consider Palestinian families holding their dead up to cameras to plead for international mercy. Or the heart-wrenching footage of children in Gaza holding a press conference outside Al-Shifa Hospital, begging the world for attention. How did this happen? How did we arrive at a moment where solidarity is flimsily predicated on parading the mutilated bodies of children?

“Compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers,” observed Susan Sontag in her study of the visual representations of violence. Compassion that is aroused through spectacles of grief, we might add, is even more unstable. Once the spectacle fades, so does the solidarity. Once the deluge of images slows, so does the haste to do something. Once the image is forgotten, the grief can be too. For decades, Palestinians have had to quietly endure the excruciation of the Israeli occupation because everyday violence is not often photogenic. If there are no images, there is no proof of the violence, and therefore no solidarity.

***

The other day I asked my friend, Mohammad, what it means to grieve publicly through this moment. Mohammad and I are both Iranian. We are both Muslim. We are both the children of a country that was ravaged by eight years of a brutal war—waged by Saddam Hussein and supported by his Western benefactors. We recognize in the images surging out of Gaza the familiar specters of militarized slaughter that once haunted our families. He offered the following observation:

It has been beyond disheartening to witness the policing of how we’re supposed to mourn or show solidarity. Palestinians share their most tragic, private moments with the world, offering their dead to prove their suffering. And still they’re scolded for how they memorialize their dead as martyrs, denied even the recognition that these lives were annihilated by a violent ethno-state.

For Mohammad, the extremes that Palestinians must publicly traverse to humanize their dead betrays how their lives are otherwise regarded as close to worthless. Families carrying the remains of their dead in bags. Teens searching for corpses of friends beneath the rubble by calling their phones. Doctors grieving the death of their own kin in the operating rooms. These are the currencies that Palestinians must trade for solidarity.

And still the premiums on compassion are too high, as lawmakers cast doubt on the integrity of reported deaths and the mainstream media equates life under a military occupation with life because of a military occupation. No matter how many pictures of blood soaked children you share, or which statistics you deploy to emphasize that a genocide is underway, it just doesn’t seem to matter. At least not where it should and to the people that it should—the powerful, that is. “The unreality of the dream that factual clarity will bring all these war crimes to an end is demonstrated every day,” Erik Baker writes at The Drift.

These, then, are the costs to the expectation that grief becomes a site of public mourning as a means of eliciting solidarity. Public grief does not evoke the same responses among different audiences. For grief to be effective, people have to be willing to view Palestinians as agents whose suffering warrants grief in the first place. To our collective moral chagrin, that is not the world that we presently inhabit, where the Israeli “grief machine” is too powerful to institutionally resist, distorting any portrait of Palestinian humanity as an assault on the history of Jewish suffering.

In addition, this constant requirement among Western audiences that solidarity must be exchanged for grief, while simultaneously reducing all representations of Palestinian personhood to the binary of villain or victim, is dehumanizing. “There is something humiliating in trying to earn solidarity,” Dr. Hala Aylan wrote in The New York Times.

We are up at night, combing through the flickering light of our phones, trying to find the metaphor, the clip, the photograph to prove a child is a child. It is an unbearable task. We ask: Will this be the image that finally does it? This half-child on a rooftop? This video, reposted by Al Jazeera, of an inconsolable girl appearing to recognize her mother’s body among the dead, screaming out, “It’s her, it’s her. I swear it’s her. I know her from her hair”?

Indeed, this is demoralizing work, especially as the war goes on. Images shared on social media are, by design, images of which their spectators will eventually tire, prompting users to endlessly scroll to feed an insatiable gluttony. As we look and look, again and again, our attention speeds up and spreads thinly. Nightly horrors, that we scroll through in the flickers of our phones, quickly turn into nightly banalities.

Lastly, this approach to eliciting solidarity, through displays of uninhibited and colossal violence, can eclipse the more quotidian forms of violence that quietly afflicts the oppressed daily. Naturally, so much of our attention is directed toward Gaza these days, as we bear witness to the newest military innovations in brutalizing innocent lives. Yet in recent weeks, there has been a marked escalation of violence in the West Bank. Since October 7th, Israeli forces and settlers have killed somewhere around 300 Palestinians in the West Bank, alongside an increasingly draconian campaign of arrests and carceral abuse (in some areas, settlers have even been putting leaflets on Palestinian cars warning them about an imminent “Second Nakba).” A politics of solidarity predicated on the spectacular will fail to bring forth the ways in which Israeli brutality permeates the fabric of Palestinian society; the everyday grief that is woven into the identity of the body politic but cannot be easily voiced or acknowledged.

***

Political organizing cannot exist without acknowledging the grief and loss that compels activism and activists into being—the loss of life, of property, of agency within a political state. Yet we cannot let public grief exist solely as a tool of political mobilization. Thus, we need to expand our conceptions of loss and grief, adopting more capacious approaches to solidarity that attend to both quotidian and spectacular violence, to both private grief and public grievance.

This capacious approach challenges the economies of grief that appropriate the private losses and pains of the oppressed as the primary currency of moral concern. The scaling of personal grief into political grievance normalizes the requirement that grief is exchanged for political activism, thereby subjecting the aggrieved to the dehumanizing expectation that they repeatedly offer us spectacular losses in return for our solidarity. In doing so, our moral sensibilities are reprogrammed to only respond to extraordinary displays of violence. This approach to solidarity, however, is not a sustainable paradigm for activism, since it relegates everyday injustices that do not rise to the status of the spectacular to the realm of politically uninteresting.

Thus, we need a politics of solidarity that is not predicated on videos of dying children, or the social-mediafication of suffering more broadly. Instead, we have to uphold the kind of solidarity that affords us the important possibility of what Christina Sharpe calls, “sitting (together) in the pain and sorrow of death as a way of making, remembering, and celebrating a life.”

Before he was killed by the Israeli military, Refaat Alareer published a poem called “If Must Die.” I knew Refaat for some time prior to the outbreak of the war and I miss him dearly—an outrageous loss that leaves an unfulfillable void behind. “If I must die/you must live/to tell my story,” Refaat wrote hauntingly in his poem. “If I must die/let it bring hope/let it be a tale.” We should heed Refaat’s words and strive for a solidarity built not around visions of horrid suffering and grief, but rather on an enduring, shared sense of humanity. A solidarity that allows its adherents space to live and to experience loss while building a better future. A solidarity based not purely on loss and grief, but on everyday compassion and acts of defiant living.

This is an incredible piece. I've been thinking about how some of the most shocking and distressing images and videos from Gaza start to feel like memes, "the shaking boy," "the mom who had 580 injections to have her now-dead baby," "the dad giving his dead child biscuits." It's like we want these short videos to be a button we can press to get an emotional response, that somehow will lead to an end to the suffering. The videos and images take on their own life, maybe leaving the humans in them behind.

Thank you for writing this. Opponents of reform often bemoan politicking in the face of atrocity; “why do we have to politicize this, can’t it just be a tragedy.” Important to remember that those most directly affected by spectacular horrors often feel the same way — the problem is that they know it can’t, or else it will happen again.

I am sorry, also, for the loss of your father.