Brainwashing Ourselves

Beyond the coconut-pill and toward the truth.

It is not surprising that it took no more than a few minutes for the assassination attempt of Donald Trump to turn into fodder for dozens of conspiracy theories. What struck me as funny though was that most of them seemed half-baked, even by conspiracy theory standards—like there were no dots to even connect, just vague gestures toward something hidden. The investment corporation BlackRock once filmed a commercial in which the shooter appears for a frame. This is evidence of …. what? No one can seem to say. People also blamed Mossad and Jews writ large. Why would Mossad want to take down Donald Trump, a supporter of Israel and Benjamin Netanyahu? Doesn’t matter.

Conspiracy theories have always been semi-fantastical, but usually they have a kernel of truth that makes them attractive. Like, yes, the government is doing shit without our knowledge and it’s probably bad.

This current crop of conspiracy theories is interesting to me because, I think, they’re the purest distillation of what conspiracy theories are—forms of denial of reality in favor of a false reality more exciting and affirming. But the more I thought about these conspiracies, the more I realized how much in common they have with more normal people’s reactions to the news.

I am accustomed to the memeification of everything, but I’ve been surprised at just how fast and total the transformation of news into self-made entertainment is these days. The Trump shooting quickly became content about Charli XCX’s BRAT (“Does anyone else kinda think that getting shot in the head and then being completely fine afterwards is, like, really, really ‘brat’ summer though?”), and fancams about Trump and Biden’s supposed romance set to Chappell Roan music.

We can see something similar in the coconut-ification of Kamala Harris—self-proclaimed leftists and cynics of the electoral system doing a better job at making her into an entertaining person and a good presidential candidate than any actual campaign has.

What anti-semitic 4Chan conspiracy theorists and the coconut-pilled have in common is a desire for a world that does not exist; they are using their imaginations to will reality into something more than it is. How fun would it be to admit that even if Kamala did replace Biden, not much would change? Not very! And so we retreat to fantasy.

Whether far-right or far-left or simply a Charli-obsessed teen, it seems the general function of social media these days is to take our quite bleak reality and, through the power of fantasy, turn it into something that feels better.

Another word for fantasy, though, might be delusion. And another might be denial.

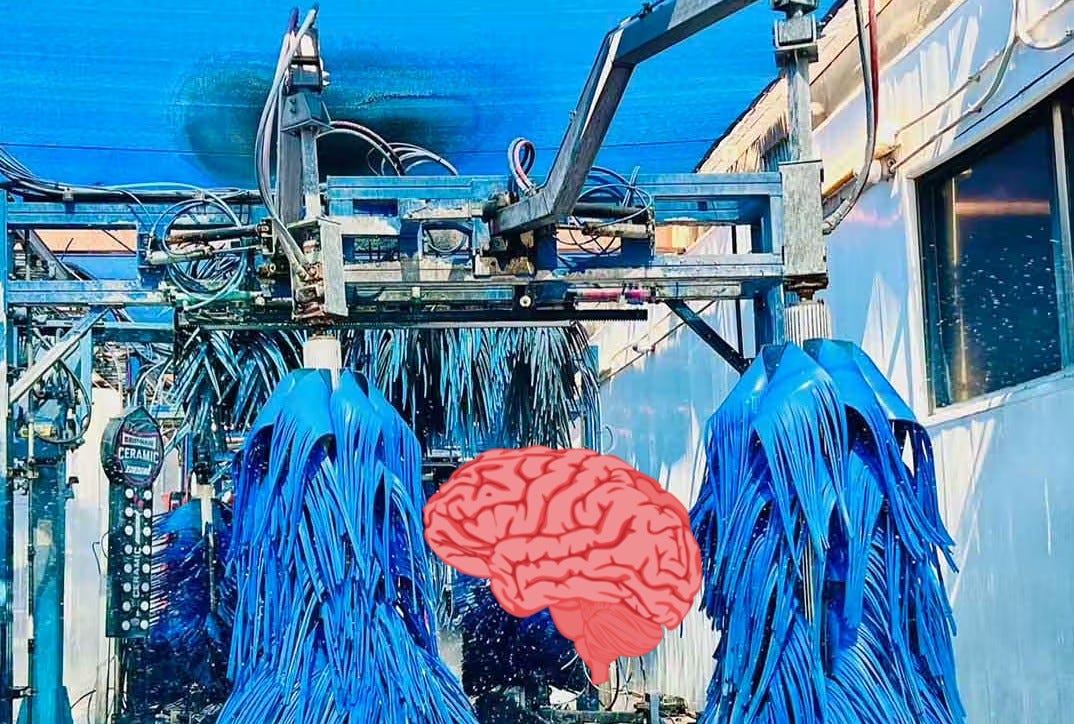

Burying our heads in the sand is not quite the right metaphor, unless the sand is filled with thousands of screens on which we project a nicer thing we’d rather see than the thing we’re burying our heads from. We are not simply ignoring the truth, we are replacing it with a self-created one.

Freud, using the example of Columbus believing that he’d landed somewhere totally different than he actually did, posits that fantasy is not simply a form of denial, but a form of wish-fulfillment. We do not create false realities because they are fun, but because we want them to be true—because the actual truth is much harder to stomach.

Everyone participates in this to a certain extent. Denial is a fundamental psychological process. The problem, though, is that denial also hurts us.

As philosopher Elinor Hållén argues in her interpretation of Freud, repression and denial ultimately, “stand in the way of carrying out one’s wishes. They compromise the enjoyment that is to be had from having one’s desire fulfilled.”

Yes, fantasy and denial make things temporarily easier, but they also disable us from pushing past our defense mechanisms to find our actual desires and enact them. Identifying that one is in denial of something, or creating delusions to cover up the truth of something, was, Freud believed, a necessary step toward finding the thing actually repressed and then being able to act on that thing. And in this this way, denial and fantasy are signs of progress.

“In short, when we deny something, we inadvertently reveal exactly what we want to hide,” philosopher Renata Salecl writes. “As a result, denial entails the widening of a crack or fault line, where a thought that we were previously not conscious of suddenly emerges. For this reason, somewhat paradoxically, Freud linked negation to the idea of freedom. He pointed out that because denial enables something to emerge that is linked to a repressed memory or feeling, we can finally start working on the significance of the repressed thought.”

There is of course nothing wrong with creating memes. But I think there are levels to the meme-ification of our world. And as of now, it feels as if we’ve crossed a line from making fun of the world and its badness to actively creating a new world in our collective psyche via our collective communication system (the internet), one in which we can ignore what we are in denial of—namely that this world, no matter who it is led by, is not going to get better anytime soon. This strikes me as a form of nihilism, which is scary.

But in the acknowledgement of our fantastical denial comes opportunity: If we take the time to analyze the fantasies we create, there we will find fault lines, cracks to force open and dive into, deep recesses to explore in which we can uncover what we are actually desirous of—things that we can then enact.