Involuntary Healing

Wilderness camps for troubled teens have received a lot of criticism. For one writer, they saved her life.

Sam Danish (they/she) is a writer and occasional wilderness therapy guide living in Brooklyn.

I spent most of my freshman year of high school at home, resisting going to school or anywhere that forced me to confront the overwhelming panic attacks that surfaced when I made the transition to high school and came out as queer. My parents are supportive and wonderful people, but they struggled to hold boundaries with me. Like many teenagers in mental health crisis, I had become manipulative, preying on their insecurities to get what I wanted, which was to avoid my life.

The worst day of my life began the day after my 16th birthday. I woke up to a knock on my door. Two burly men entered and told me that my parents had chosen to send me to a therapeutic wilderness program in Vermont. From the haze of sleep, my mind raced towards panic and reached for escape routes. I looked at the window briefly thinking I might be able to jump but quickly ruled that out. I registered from what they said that my parents would meet us in Vermont. And so my mind focused on that. I would be able to convince them to take me home.

I met my parents at the program headquarters. And after failing to convince them to unenroll me, my panic became anger, and I told them that I would never forgive them if they made me stay. As they said their tearful goodbyes, I was taken into a warehouse in the back of the building. Once I was outfitted with camping gear, I hiked out to the group of teenage boys, and was handed the curriculum of the program. It included what are called “hard skills,” such as primitive fire-making techniques that would be the backbone of the “soft skills”—the therapeutic process. To some extent, I was in control of how long I stayed in the program. I learned the fastest someone had left was 45 days, the slowest was four months.

I spent the next nine weeks backpacking in the Vermont state forests, learning wilderness survival skills and undergoing a form of cognitive behavioral therapy under the supervision of what are called guides and a licensed therapist I saw twice a week. My parents went through their own concurrent therapeutic process back home, and we met midway through the program for a family workshop.

That first night, still in the haze of panic and looking for escape, I walked off not sure where I was going. The lead guide followed for hours in the woods. He never forced me back. He just bluntly presented me with my options. My parents were gone, and I was in the woods. Later someone explained to me that “runners” often want to test boundaries. I realize now that I was testing John to see if he would force me, but instead, he just walked with me. And so I went back and started my journey.

Being sent to a wilderness program usually means you have hit rock bottom. Many guides have a seemingly endless well of empathy and willingness to forgive because they have seen so many students go from that place to a more assured version of themselves. I know of students who physically assaulted guides they later became deeply close to.

The reputation of these programs is overwhelmingly negative in large part because of the extremity of their premise. Forcing someone to live in the woods as treatment is hard for most people to understand. But it’s an experiential form of therapy. Instead of talking about all the problems you’re facing for an hour each week, the problems and the solutions are presented in real time, with constant feedback given. There is therapeutic work that is possible when you aren’t given a choice, but instead must confront your problems head on. And that provided me perspective and engendered real, lasting, positive change in me that wasn’t happening in traditional psychotherapy.

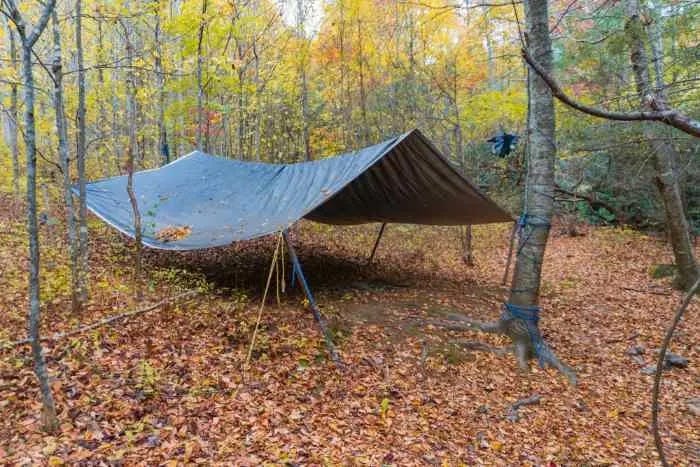

The woods are dynamic, and there are always new challenges that force you to figure out solutions. For ten days at a time we went on expeditions where we hiked every day—setting up camp and making our fires from scratch, setting up shelters, cooking our own food.

Everything feels like a metaphor in the woods, but especially the rain. For me, there was nothing as hard as being wet for days on end with no way to get dry. It made everything more difficult, from hiking to starting a fire. I always wanted to shut down, but in the woods, you just had to keep going. Eventually the sun would come out and dry everything in less than an hour. I got better at existing in discomfort, and I went from feeling like everything was impossible to feeling capable and confident.

And then I finished, and I was thrust back into the world I had left. The next eight years of my life, I slowly packed away the wilderness. It became a secret I kept, like all my camping gear stored in the basement of my parents’ house. The sense of pride and accomplishment I felt turned into a fear of being judged for being a “wilderness kid.” When dark moments came, I drew on the lessons I learned, but I didn’t tell many people about it. The few times I did, I got looks, like I must have been crazy. People assumed that it had to have been traumatic. It was lonely to have no one who understood the gravity of the experience.

Then the pandemic forced me to spend copious amounts of time at home with my parents, reminding me of that period leading to wilderness. I realized I had always been afraid of returning to a place where I needed to go back to that kind of program and didn’t entirely understand why it had worked for me. I felt the need to revisit it for closure, so I applied to work as a guide. The program had recently started an all-gender group and hired a trans therapist. I had come out as trans in college, and I became a designated guide for that group. It felt like a true calling to go back.

Returning to work as a guide was seeing the backstage of a show that had helped make me. I learned that guides were trained in a process of “pattern exhaustion.” Each student was observed for several negative behavior patterns such as victim, blamer, intimidator, pleaser, each with their own “positive intention,” i.e. some need or desire that the student was seeking. For instance an “intimidator” was someone who tried to scare others because they felt unsafe, and people fearing them gave them a sense of safety. Grounding all the treatment was the belief that students are inherently good and want basic things like physical and emotional safety. Our job as guides was to show them how they could still get those needs met.

The program did not let diagnoses define students. Panic and anxiety diagnoses had allowed me to avoid everything. Saying I was having a panic attack became a way to escape a hard situation. I could go to the school counselor's office, or go home. It didn’t force me to address the underlying reasons I was seeking that escape or find ways to live my life with anxiety. Pattern work gave me a sense of agency over my mind. I could accept that I play the “victim” and “blame” but that those are just tools I am using to get my needs met. I could find better ways to do that and give my students the choice to find better ways too.

I worked with many “victims” in a group of mostly young queer and trans teens. What’s hard about working with victims is that to truly help them you must deny them the support they want. They are asking for it because they feel that they are not capable of doing it on their own, so as guides, we learn to give the support that helps students understand their own capability. Many students initially struggle with the basics of camping. In the first stage of the program, the emphasis is on showing them how to take care of themselves rather than doing things for them. You show a student how to set up their tarp and teach them the knots, but you don’t set it up for them. To show them their capacity, I had to refrain from rescuing them. Rescuing them would have reinforced that I believed they weren’t capable of it. It’s an odd form of care, and many parents of victims will rescue them because it doesn’t feel good to let your child struggle.

Guiding is about keeping students safe but allowing for discomfort and challenge. It took faith in my co-guides who had seen this work, and a memory of my own time being guided, to observe students go from breaking down in tears and yelling to confidently building fires and navigating using a compass and map on their own.

I have been in therapy since I was nine. The two months I spent in this program were more effective than years of talk therapy. The biggest breakthroughs happened in the middle of the woods, often while extremely wet and dirty, having someone call me on my bullshit in ways my therapists never could. Ultimately in therapeutic relationships, that person works for you, and you can quit, so you’re not forced to confront what is actually holding you back. Truly finding mental wellbeing has not been a comfortable or pleasant experience for me, but it’s worked. Seeing it work for students I guided further cemented this belief.

The relationship between guide and student is intense. To be a good guide is to first demonstrate to someone that they can trust you with their physical and emotional safety. Some students have not had this in their lives. Their boundaries have been violated and they struggle to trust anyone. Building this “rapport,” as guides call it, allowed students to feel safe with me when I told them a hard truth and pushed them into places of discomfort.

One element of guiding is holding standards such as making sure students are completing meals, drinking water, taking care of their gear, and completing their roles in the group such as leading the group in certain parts of the day or cooking for the group. Holding standards is often a huge shift for students who have either faced punitive systems at home or had no structure or boundaries. Another element is reflecting students' behavior back to them or giving feedback. Having guided and been guided, it’s like no other relationship I've had. And to do that for others feels like a true act of love because it isn’t self-serving. To guide means to have students often vacillate between being angry with you and then seeking your approval. I had one particular student say to me when I was giving them some hard feedback, “You’re my favorite guide, but only when you’re not here.” I remember it because it is exactly how I felt about my best guides.

The program I attended and worked at is not perfect. Often it is the strength of the guides and therapists who work there that make the program work. Guides are underpaid and are contracted labor, so I ran into guides who did not have enough training and ones that should not have been guiding. Many other programs, in a constellation called the “Troubled Teen Industry” by critics, function with little oversight in states such as Utah which have fewer laws about minors’ autonomy. Wilderness therapy and therapeutic boarding schools have come under more scrutiny after Paris Hilton wrote about her harrowing experience in one of them. And a TikTok trend called #BreakingCodeSilence, named after the practice in some programs of forced isolation and silence, allowed many to speak up about negative experiences with wilderness therapy.

These programs need oversight, standards, and rigorous study. I believe a big reason the program I worked and attended worked for me and others is that once at the program, everything was grounded in consent. There is absolutely no forced isolation or punishment and restraint is used rarely and only in cases when a student is an immediate danger to themselves or others. I only used restraint once as a guide and it was to prevent a student from self-harming. I never made a student do anything, physically or verbally. I simply presented choices as they were once presented to me.

Returning, I had to come to terms with the involuntary nature of the program. I did not choose it and neither did most of the students I worked with. Many of them were as resistant as I was initially, but all of them saw at least some of the value in it towards the end. I initially didn’t tell other guides that I had been in the program. I felt embarrassed about having been in such a dark place that my parents believed I could no longer be trusted to make decisions about my own life. When I opened up to fellow guides and students about my experience as a student, there was often curiosity and disbelief that I would choose to come back. I explained that I believe that being sent to the program was not just about my inability to live my life on my own but also an admission of my parents that they were unable to parent me. My family system could not give me the support I needed and neither could traditional therapy.

When I think back on where I was when I was sent to the program, I realize that I would not have trusted that version of myself with my own life. I don’t see an alternative to the decision that my parents made that would have worked. My mind was constantly seeking the easy escape of staying home, and there was no way I was going to choose the hard path of finding resilience. I wanted someone to fix everything.

Often people ask me if the experience was traumatic. It was the most challenging thing I’ve ever done, and I often felt very overwhelmed. But that challenge helped me build muscles that allowed me to weather the challenging things that came after I left. I think that there’s a difference between being challenged and being harmed. It’s a slippery slope, but there is a distinction.

When speaking to one of the therapists, they said one of the biggest issues they had with the work was that the parents often came in with specific expectations of how they wanted their kids to be after. They explained to me that often their role is explaining to students that their parents will probably not drastically change, but that they want to help students be ready for when they are in control of their lives and not under their parents’ control. That’s why the therapist often recommended further treatment for the student primarily because if they went back home to their family, they would end up back where they started. The initial breach in consent had allowed me and would hopefully allow the students I worked with to survive once they were making their own choices.

If so many families are reaching this breaking point that it creates a multi-billion dollar industry, there is a need that must be met. Families and schools alone are not capable of addressing the childhood mental health crisis alone. I worked with a group of mostly trans teenagers. They were angry and blamed the world for everything because they were scared and felt alone. They raged at cisgender guides who even slightly misstepped and found comfort in pop mental health language from social media which they used to avoid challenging moments, like the words “anxiety” and “panic” had done for me. The advice I had the hardest time giving to students was that the world was not going to suddenly become an easier place to live. Unfortunately, they had to become more resilient.

I want more people, children and adults, to have the opportunity to access programs like the one I went through. I believe that there are moments when involuntary and immersive therapy allows for deeper work, but it’s dangerous and unethical that these programs are motivated by profit, that the outcomes are measured in parent satisfaction, and that parents themselves are not going through a more extensive therapeutic process as the child. Despite all that, I’ve yet to find anything like it. To this day, I keep a steel striker and a quartz rock by my bed to remind me that when things feel impossible, I can still make a fire.

So a psych ward for kids but outdoors. What an incredible amount of privilege to go through that, see/hear so many victims of abuse and trauma at these places and turn around and say well it was really helpful for me personally! Then to become complicit in it as an adult yet in the same breath say they are unethical? You cannot reform these places that are literally modelled after prisons and psych wards. What a disappointing read.

Involuntary “treatment” is abuse. Like the author, I went through a wilderness “therapy” program. I still have nightmares about it several years later.

These programs are for-profit and designed to do just that, make a profit. They’re back by little or no evidence. Rather, studies are being done and are concluding that being kidnapped and taken into the woods is absolutely traumatic and unethical.

Let’s not promote this troubled industry. Let’s rise up against it. Thousands of voices of thousands of survivors who went to programs like this one are calling for a shake down. And people are listening. While this author ignores their cries.