The Brutal Honesty of Old Prescription Drug Ads

Over the years, ads have shifted the blame for mental distress from society to the individual.

Today, if you are prescribed a psychotropic medication, you’ll likely have to meet diagnostic criteria that place you in one or several of the hundreds of available disorders in the DSM-V. And, with hundreds of possible diagnoses, and hundreds of mental health meds being manufactured by prescription drug companies, the competition to ensure you chose the right, or most profitable drug, is intense. Television and magazines are filled with advertisements alerting us to the myriad mental health meds available to us. And all of them follow a similar script: you have a disorder that can be found in the DSM, it’s due to a chemical imbalance, and it can be fixed by a drug.

Advertisements, it goes without saying, are not psychiatric science, and yet we’ve internalized what they tell us as the truth. The “chemical imbalance” model of mental illness, most common when talking about depression, has not been proven by any study. It was a marketing tactic employed by the makers of antidepressants. Even the very pro-drug American Psychiatric Association’s official position on psychiatric disorders states that disorders, “result from the complex interaction of physical, psychological, and social factors and treatment may be directed toward any or all three of these areas.”

Despite most scientists not being on board with the chemical imbalance theory, the advertisements worked to change our minds about our own brains. Though there’s no study to quantify what most Americans believe, it’s safe to say that the chemical imbalance theory of mental illness is the most prevalent—ADHD, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder are all simply functions of wacky brain chemistry.

But not that long ago, America had a very different view of mental health disorders and their causes. And we can see how rapidly things have changed by looking at the ads used to sell Americans our drugs.

From the early 1900s until the 1960s, prescription drug ads were, in many ways, more honest about the causes of our distress. We weren’t inexorably broken; we were stressed, depressed and irritable because of the conditions of our daily lives.

Though an ad encouraging a doctor to prescribe a woman Dexedrine (a stimulant still available today that functions much like Adderall) so that she can make breakfast and take care of her kids is undoubtedly sexist, it is also more truthful—the reason people need drugs is not because of some inherent brain condition that was only discovered a few decades ago called ADHD, but because our lives demand too much from us.

A 1950s ad for Serpasil (a precursor to modern antipsychotics) promised the drug would “raise the emotional threshold” for people who are, “without some help, incapable of dealing calmly with a daily pile-up of stressful situations.”

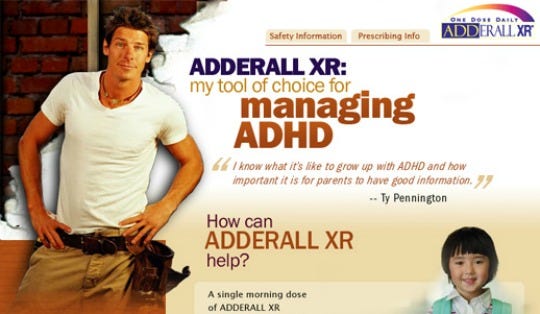

Today, ads remove all of life’s context and focus simply on the diagnosis. Mood stabilizers and antipsychotics help not because you are a stressed housewife, but because you have bipolar disorder. Amphetamines are needed not to cure your suburban boredom, but because you have a medical condition called ADHD.

Modern ads, for comparison:

Though I wouldn’t say previous generations’ ads were morally better, they provide insight into how we viewed our lives and the distress modern living caused. And the connecting theme of all the ads—whether Ritalin, antipsychotics, or antidepressants—was that we felt out of control. Wives could no longer take care of their families, husbands felt stuck at their jobs, children were failing at school.

Collectively, the ads said: “life sucks, this drug can help.” Today prescription drug ads are telling us the opposite: “life isn’t the problem, your brain is.” This shift in advertising tactic tracks a shift in where we as a society place the blame for our anguish. The chemical imbalance theory, as shaky as it was scientifically, became our predominant mental model because it allowed us to ignore that it was life’s circumstances, not our own brains, that were the problem.

It’s no coincidence that this theory came to prominence in our era of neoliberalization—the 1970s and 1980s. This is when institutions like unions were dismantled, industrial jobs vanished, and the era of the American automaton was born—we were disconnected from community, from family life, from care provided by the state. Though there was no secret meeting to decide to re-market these drugs to fit our neoliberal era, it makes sense that a societal shift from viewing life and its problems collectively to viewing them individually would be reflected in our culture and its advertisements.

Of course, pining for a bygone day of pharmaceutical advertisements is not a solution to this new, neoliberal focus on the individual. But they do show that we didn’t always think this way, that we did at one point believe that society was at least partially to blame for our distress. Perhaps one day our thinking will shift again.

More old ads:

Check out an archive of old prescription drug ads here.

This is wonderful writing on a critical topic. thank you