What Happened to the Communal, Revolutionary Spirit?

Can an anarchist manifesto from 2007 show us a way out of our mental health crisis?

Gareth Watkins is a writer currently based in Manchester, UK. He has written for The Los Angeles Review of Books, Tribune, Commune, Vulture and MEL.

We’re miserable. Individualized solutions are at best a crapshoot, quite often unscientific fads, and on occasion more dangerous than the illnesses they were created to cure. The alternative is the “structural problem” model of mental illness, which has much to commend as a base to work from but can easily become an excuse for inactivity and a kind of performative hopelessness in which your sheer depravity and squalor become an indictment of the system and getting better is selling out. If you want, or have, to get better then you find yourself in the Catch-22 Johanna Hedva identifies in Sick Woman Theory: “how do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can’t get out of bed?” And how will we ever get out of bed while there are still banks?

What is needed is something that is neither individual therapy nor holding out for a global revolution that the sheer level of mental illness in our society is making increasingly unlikely. A way for people to collectively work through the damage that living in this world inflicts that goes beyond sharing our pain and towards making material changes in our lives and being able to act politically.

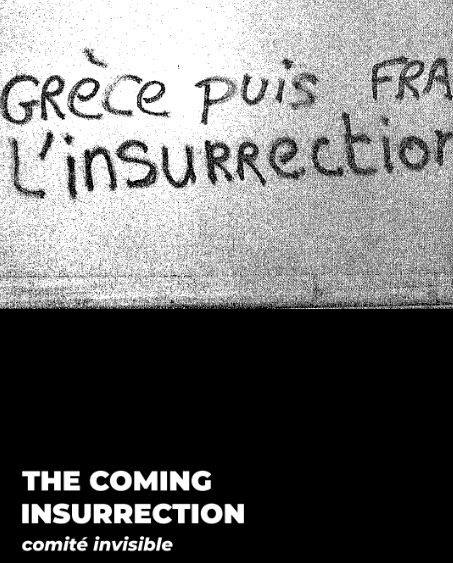

The Coming Insurrection, authored by a still-anonymous “Invisible Committee,” was one of the last gasps of the anti-authoritarian, anti-globalization, anti-capitalist era of the radical left that ran from the nineties to 2010s: No Logo, the Battle of Seattle, Adbusters, Atari Teenage Riot, Giorgio Agamben, Change The World Without Taking Power, Propaghandi, Noam Chomsky, Refused, Hardt and Negri’s Empire, then finally its culmination in Occupy. The mood was more anarchist than Marxist, organized labor was barely mentioned, the proletariat replaced by a vague global multitude of activists, squatters and hackers.

The book pushed the anti-authoritarian logic and aesthetic of that time as far as it would go. Every form of organized politics was to be dismissed as reactionary (“The first obstacle every social movement faces (...) are the unions and the entire micro-bureaucracy whose job it is to control the struggle,”) replaced with the committee’s reimagining of the commune as the core unit of revolutionary struggle:

“Communes come into being when people find each other, get on with each other, and decide on a common path. The commune is perhaps what gets decided at the very moment when we would normally part ways.”

For most, the term commune denotes an intentional community in a fixed place—anything from Oneida to the Paris Commune to The Farm. The Coming Insurrection’s innovation was to see small, temporary configurations of people as being just as much communes as Kronstadt—something that the late David Graeber would also often stress in his work. One of the few examples of the ideas in the book being put into practice, the Tarnac Nine—a French “terrorist cell” who were in fact a group of intellectuals living together on a farm—numbered, as their name suggests, nine people. As a side note, it’s possible that the Tarnac Nine and the Invisible Committee might be one and the same.

Over two chapters and a dozen separate injunctions (twelve “rules for life” if you will), the committee lays out the ethics of these communes (“get organized in order to no longer have to work’, ‘flee visibility’, ‘organize self-defense”) while remaining light on details of the structures that they are proposing in order to give their readers enough space to find what works for them

The experience of the Tarnac Nine could point towards one of the ways that a commune would function in practice: they were a group of five women and four men, all well-educated and on paths to lives that were as comfortable as the modern world would allow who collectively decided to uproot themselves to the minuscule village of Tarnac (population 341). There they established a communal farm, a grocery and a bar. They organized a delivery service for housebound residents and ran a cinema club. They became part of their local community. If two of them hadn’t allegedly committed vandalism against a railway line the world would have in all likelihood never heard of them. There may be hundreds or thousands of such tiny communes around the world, some inspired by The Coming Insurrection, many just people who grew sick of life under capitalism and wanted something different.

The Coming Insurrection has one foot firmly planted in a school of contemporary left-wing thought known as Communisation Theory. Extremely briefly, this doctrine holds that:

“A revolution is only communist if it changes all social relationships into communist relationships, and this can only be done if the process starts in the very early days of the revolutionary upheaval. Money, wage-labour, the enterprise as a separate unit and a value-accumulating pole, work-time as cut off from the rest of our life, production for value, private property, State agencies as mediators of social life and conflicts, the separation between learning and doing, the quest for maximum and fastest circulation of everything, all of these have to be done away with, and not just be run by collectives or turned over to public ownership: they have to be replaced by communal, moneyless, profitless, Stateless, forms of life.”

Even briefer: be the change that you want to see in the world. Rather than seizing power and entering a transitional phase which has most if not all of the psychologically deleterious aspects of capitalism but in which communism is the end goal, as the Bolsheviks did during the October Revolution, we can create post-capitalist institutions today.

Of course, the idea of a bunch of people living together, mutually supporting each other is hardly new, or even radical. Squats and punk houses exist in every city, queer folks have been forming “communes” for centuries (this site’s own editor talks about their experience in a place that would meet the Invisible Committee’s loose criteria for being a commune here). There are video games to simulate the experience. NFT marks have practically given up on trying to argue that they are investments—now a Bored Ape is a ticket to exclusive parties. Even our complete ideological opposites dream of trad-villages of organic farms and ruddy-cheeked Aryan maidens pumping out towheaded white children. Humanity has always had its Land of Cocakyne and Big Rock Candy Mountain. Our ideas of a good, mentally healthy life are surprisingly consistent, and at the center of them all is always community.

The psychological benefits of friendship have been studied and pop-psychologized to the point that I hardly need to repeat the fact that close friendships have a “prophylactic effect” on mental illness. Nor that, twenty-two years after Bowling Alone and its diagnosis of a “collapse in American community,” friendships are declining in both quantity and quality. With the possible exceptions of our romantic partners, the interactions we have are too few and more often digital than physical, more based around shared activities than a commitment to help each other through an increasingly hostile 21st century. We’re always-already alienated from our time spent socializing: whether we’re at a dive bar or driving range, it’s re-creation of our ability to work. We’re refueling ourselves for another forty hours at our silly little email jobs. Most of us have friends, but the epidemic levels of mental illness that having friends should prevent shows that we aren’t getting something vital from those friendships—they’re all empty calories and no vitamins.

For all its Gallic bluster and recent-convert earnestness, The Coming Insurrection is ultimately a book about friendship. They are the first to admit it: “We're setting out from a point of extreme isolation, of extreme weakness.” Those friendships don’t have to lead to literal communes of the kind the Tarnac Nine lived in—your shared house, your college dorm, your workplace, anywhere that a small number of people are in constant close proximity can be a commune provided that you all remember the Committee’s first rule for life: don’t back away from what is political in friendship.

“We've been given a neutral idea of friendship,” they say, “understood as a pure affection with no consequences.” What should those consequences be? For most of us, the most pressing need is to undo the damage that has been done to us from life under capitalism, which means communally addressing the material reasons for that damage—overwork, debt, poverty, isolation, unemployment and so on. This doesn’t mean that each commune should become a group therapy session, but that they are, “organize(d) for the moral and material survival of each of their members.” In practice, each comrade is fully committed to doing whatever it takes to get all others to a point where the psychological harm of capitalism has been detoxified—maybe creating a ‘disalienated space’, as this article dealing with very similar themes puts it, maybe, “get(ting) organized to no longer have to work,” (The Coming Insurrection’s fifth rule for life).

While it is possible to deal with mental illness alone, even with much-hated techniques like CBT and psychopharmacology, the formation of communes and the creation of spaces outside of capital, however temporary, directly addresses one of the core problems of living in our society as civilization winds down. It is increasingly hard to go it alone, hence why so many people live in shared homes or with their parents, and even in these situations it's difficult to build political friendships, where our bonds with each other become sites of resistance rather than recreation. While it’s usually a terrible idea to make sweeping generalizations about the causes and cures of mental illness, I will say this: the vast majority of psychological problems in our society stem from feeling socially isolated, from the incompatibility of human life with capitalism and from feeling powerless to change our situation. Within a commune, isolation is replaced by the kind of deep friendships that actually nourish us.

So let’s return to that first question, which I often find myself asking whenever I close a big and important book of theory that I hoped would point to some way out of the world as it is: now what? Now, if a solo trek from one pill to another isn’t working, if you can’t hold out for a coming insurrection, then you need other people, and in all likelihood they need you. There is a lot that is dated about The Coming Insurrection, and its earnestness will easily be dismissed as ‘cringe’ by a left that is all too often a youth subculture rather than a vehicle for changing the world, but there’s something there worth keeping.

Although its authors intended to create a manual for ultra-left political praxis, to do this they needed to resolve the contradiction between politics and mental health—how do we have a revolution with broken people and how do we fix ourselves until after the revolution? Their answer is that we don’t wait, that in communes we have a structure that can provide the mental health benefits of a post-capitalist world, relationships that go beyond recreation and into the political. The book’s final line, “all power to the communes!” may be ill-suited to a cynical, irony-poisoned, all-but-defeated era of the left, but, honestly, all power to the communes.

I think the actual process of working with comrades to build socialism is key as well, not just waiting around for revolution.